An uneven basement floor rarely announces itself dramatically. More often, the problem becomes obvious only after finished flooring is installed and small dips begin translating into visible gaps, stressed joints, or a surface that feels slightly off underfoot. Furniture exposes the issue even faster, especially when a cabinet rocks or a table refuses to sit flat. What seemed minor during construction becomes difficult to ignore once the space is finished and in daily use.

Self-leveling concrete is frequently presented as a straightforward solution. In the right conditions, it performs exactly as promised, creating a smooth substrate ready for tile, vinyl plank, or laminate. In the wrong conditions, however, it becomes a thin cosmetic layer placed over movement or moisture pressure that continues beneath it. When that happens, cracks reappear, separation develops, and the original problem returns in a more expensive form.

The real decision is not whether self-leveling compound works. It does. The decision is whether the floor beneath it is stable enough for the material to succeed. Understanding that distinction prevents wasted effort and prevents turning a surface correction into a structural mistake.

Why Basement Floors Become Uneven

Basement slabs change over time because the materials beneath them change. Concrete itself is rigid, but the soil supporting it expands, contracts, and settles. Even in well-built homes, minor variation across a basement floor is common after years of seasonal moisture shifts and natural ground compaction.

During the curing process, concrete undergoes shrinkage as internal moisture evaporates. This early-stage contraction can create subtle dips or hairline cracks that remain stable once the slab has fully cured. These imperfections are surface-level in nature and do not indicate ongoing structural movement.

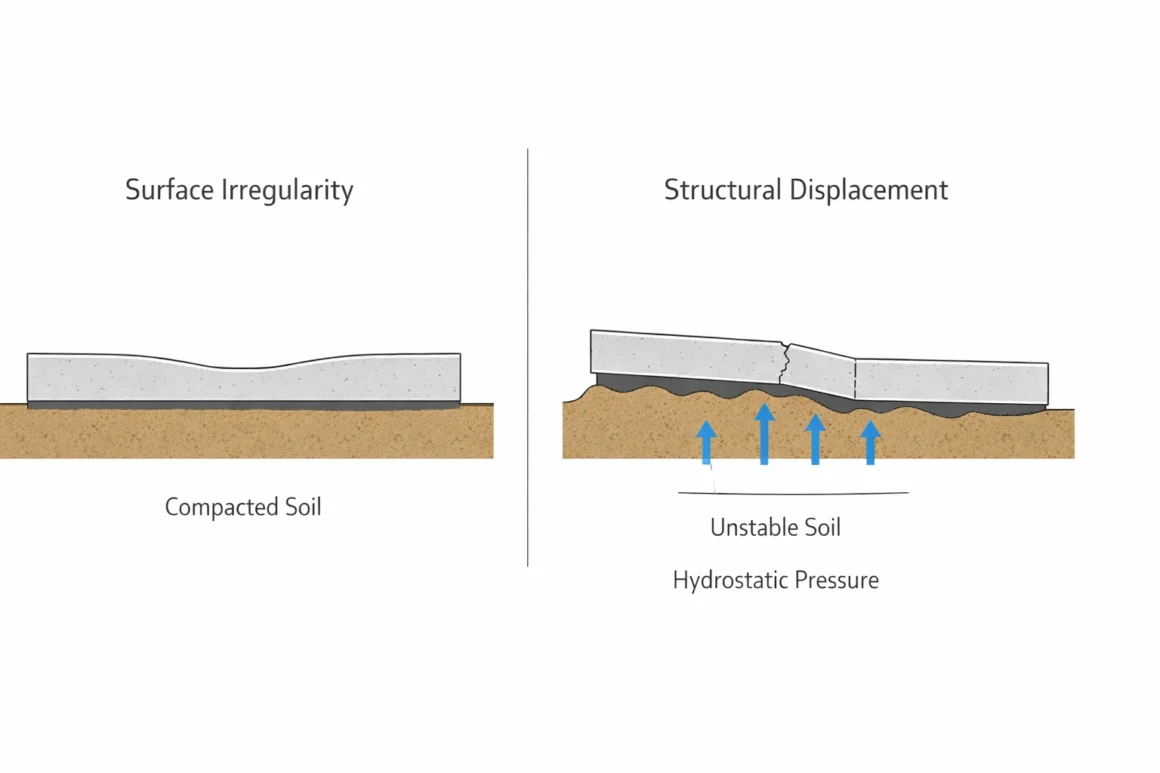

Settlement beneath the slab presents a different dynamic. If the soil was unevenly compacted during construction or gradually shifts over time, sections of the slab may sink at different rates. The result is a floor that slopes slightly in one direction or contains localized depressions. In older homes, modest settlement is not unusual, but active or accelerating displacement signals a deeper concern.

Moisture pressure adds another layer of complexity. Groundwater accumulating beneath a basement floor exerts upward force against the concrete. Over time, this hydrostatic pressure can contribute to cracking, efflorescence, or localized lifting. When moisture remains unresolved, any surface correction applied above it must withstand continuous pressure from below.

In many basements, these forces develop slowly enough that homeowners adapt to the slope without realizing it. The floor feels normal until something rigid — tile, cabinets, or shelving — makes the variation visible.

The critical distinction lies between surface irregularity and structural displacement. A shallow dip spread gradually across the room reflects surface variation. Noticeable height differences between slab sections, widening cracks, or persistent damp areas suggest movement that extends beyond cosmetic correction. Self-leveling compound corrects surface variation, but it does not resolve structural displacement beneath the slab.

When Self-Leveling Concrete Actually Works

Self-leveling concrete performs reliably when the slab beneath it is stable, dry, and no longer shifting. Its purpose is refinement rather than reinforcement. When the unevenness is limited to shallow depressions or surface waves within the manufacturer’s thickness range, the compound flows into low areas and cures into a continuous, flat plane.

Most products are engineered for pours between 1/8 inch and 1 inch thick, although specific limits vary. Within this range, the material bonds securely to properly prepared concrete and provides an even substrate for finished flooring. Attempting to correct deeper structural drops with repeated layers increases cost while failing to address the underlying cause of displacement.

Surface preparation determines whether the compound performs as intended. The slab must be mechanically sound, free from debris, and properly primed to ensure adhesion. Dust, adhesive residue, or unaddressed moisture create separation points that compromise the bond between layers. When leveling compound delaminates, the failure typically traces back to preparation rather than the product itself.

In stable basements with minor unevenness, self-leveling concrete provides a practical finishing solution. It enhances flatness for materials such as vinyl plank, laminate, or tile, all of which depend on a smooth substrate for long-term durability. Under these conditions, the compound improves performance without altering the structural behavior of the slab below.

When Self-Leveling Concrete Fails

Self-leveling concrete fails for predictable reasons. The material itself is not fragile, but it is thin and dependent on the stability of what lies beneath it. When movement, moisture, or structural stress continues below the slab, the compound becomes the visible layer that absorbs the consequences.

Active cracks are the clearest warning sign. A hairline crack that remains unchanged over time is usually cosmetic. A crack that widens, shifts vertically, or continues to reappear after patching signals slab movement. Pouring leveling compound across an active fracture does not neutralize the stress line; it simply bridges it temporarily. As the slab shifts again, the compound fractures along the same path.

It is rarely the dramatic crack that creates long-term frustration. More often, it is the subtle movement that continues just enough to undermine any cosmetic fix placed above it.

Significant height differences between slab sections present a similar limitation. When one portion of the basement floor has settled more than another, the issue is not surface irregularity but displacement. Leveling compound can fill the gap visually, but it does not re-support the slab. Over time, gravity and continued settlement reopen the separation.

Moisture introduces a slower but equally destructive form of failure. Persistent dampness beneath the slab creates upward pressure and interferes with adhesion. Even when a primer is applied, recurring moisture weakens the bond between layers. The result may appear months later as hollow spots, bubbling, or delamination. The compound detaches not because it was poorly mixed, but because the environment beneath it remains unstable.

In each of these scenarios, the pattern is consistent: the compound reflects the condition of the slab rather than correcting it. When structural or moisture issues are active, surface leveling becomes a temporary mask instead of a solution.

Understanding where leveling compound succeeds or fails makes cost evaluation more realistic. Material price alone does not determine value; the condition of the slab does.

Cost Reality: DIY vs Contractor Leveling

Cost is often the first question homeowners ask, but price alone rarely tells the full story. The depth of the irregularities and the total square footage involved usually determine how much material is required — and how quickly a small project turns into a larger one.

Self-leveling compound is typically sold in 40–50 pound bags, covering roughly 40 to 50 square feet at 1/8 inch thickness. As thickness increases, coverage decreases proportionally. A floor that requires 1/2 inch correction across 400 square feet may require four times the material of a shallow skim coat.

At an average material cost of $30 to $50 per bag, a small basement with minor dips might be corrected for a few hundred dollars in compound alone. Larger spaces with deeper depressions quickly move into the $800 to $1,500 range in material costs before factoring in primer, tools, and surface preparation supplies.

Primer is not optional. Most manufacturers require it to ensure proper bonding, and skipping this step often leads to delamination. Mechanical preparation, patching of cracks, and moisture mitigation may add additional expense depending on the slab’s condition.

Labor is where the cost difference between DIY and professional work becomes more apparent. Contractors typically charge between $3 and $8 per square foot for floor leveling, depending on region and slab condition. This includes surface preparation, material handling, and controlled pouring. While the per-square-foot rate appears higher than DIY material costs, it reduces the risk of improper mixing, inconsistent thickness, or bonding failure.

The cheapest approach is not always the lowest upfront cost. For shallow, stable irregularities, DIY leveling is financially reasonable. For widespread or deep correction, repeated material purchases and potential rework can exceed the cost of hiring a professional from the start.

Preparation and Execution Reality

Most self-leveling failures are not caused by the material itself but by conditions surrounding its application. The compound is designed to flow into low areas and settle evenly, but it does not compensate for poor preparation, incorrect mixing ratios, or uncontrolled working conditions. When problems occur, they usually trace back to what happened before the pour began.

Moisture is the first variable to assess. Concrete may appear dry while still transmitting vapor through its surface. Simple surface dryness is not enough; persistent moisture beneath the slab interferes with bonding and can weaken the cured layer over time. Moisture should be verified rather than assumed. Simple plastic sheet testing can reveal trapped vapor, while professional vapor emission testing provides quantitative confirmation. Surface dryness is not proof of internal stability.

Surface preparation also determines long-term performance. The slab must be structurally sound, free from dust, oil, adhesive residue, and loose debris. In some cases, light mechanical abrasion improves bonding. Primer, when specified by the manufacturer, creates the interface that allows the compound to adhere uniformly rather than separating at thin edges.

Execution speed is another overlooked factor. Self-leveling products have limited working time, often between 10 and 20 minutes depending on temperature. Large basement areas require careful batch coordination so that successive pours blend seamlessly. Delays between mixes can create ridges or cold joints where material begins curing before adjacent sections are placed.

Temperature influences curing behavior as well. Cold environments slow flow and extend curing time, while high temperatures accelerate setting and reduce workable time. Inconsistent environmental conditions across a basement can lead to uneven results, particularly near exterior walls or garage-adjacent foundations.

When preparation is thorough and execution is controlled, self-leveling compound behaves predictably. When these variables are ignored, the material simply reveals the weaknesses of the process rather than correcting them.

A Clear Decision Framework

Self-leveling concrete is a finishing solution, not a structural correction. When the slab beneath it is no longer shifting, free of moisture intrusion, and structurally sound, the material performs exactly as intended. It refines the surface, supports modern flooring systems, and improves flatness without altering the behavior of the foundation itself.

The situation changes when unevenness reflects movement or pressure from below. Active cracks, vertical displacement between slab sections, or persistent dampness indicate conditions that leveling compound cannot resolve. In those cases, a surface layer addresses appearance while the underlying stress continues.

Before pouring, step back and assess the floor’s stability, any signs of moisture intrusion, and how deep the irregularities actually run. If all three fall within safe limits, self-leveling concrete is a practical and cost-efficient solution. If any remain uncertain, further assessment prevents turning a manageable issue into a repeated repair cycle.

Basement floors do not require perfection. They require integrity. Leveling compound improves flatness only after integrity is confirmed. Applied at the right moment, it completes the surface. Applied too early, it simply follows the movement beneath it.

Note: This article addresses surface-level slab correction. Structural foundation movement or severe hydrostatic pressure should be evaluated by a licensed structural professional.

Frequently Asked Questions

How thick can self-leveling concrete be poured in a basement?

Most products allow pours between 1/8 inch and 1 inch per application. Some formulations support deeper fills, but exceeding manufacturer limits increases cracking risk and may require multiple controlled layers. Thickness should always align with product specifications and slab condition.

How long does self-leveling concrete take to dry?

Initial set typically occurs within a few hours, but full curing time varies by product and environmental conditions. Light foot traffic may be allowed within 4 to 6 hours, while flooring installation usually requires 24 hours or more. Temperature and humidity directly influence curing speed.

Can self-leveling concrete be applied over cracks?

It can bridge hairline cracks that are stable and inactive. It should not be used to cover widening, shifting, or structural cracks. Active movement will transfer through the compound and cause visible fracture along the same line.

Is it cheaper to level a basement floor yourself?

For shallow and stable irregularities, DIY leveling often costs less than hiring a contractor. When large areas require deep correction, material volume increases quickly and the cost difference narrows. Rework caused by improper preparation can eliminate initial savings.

Do you always need primer before pouring leveling compound?

Yes. Primer improves adhesion and reduces the risk of delamination. Skipping primer compromises bonding and frequently leads to separation between the compound and the slab.

Author & Editorial Review

- Author: Perla Irish — design writer covering interior materials, structural surface behavior, and practical home renovation decisions, with research-based analysis of basement flooring systems and slab performance.

- Editorial Review: This article was reviewed by the Living Bits & Things editorial team to ensure clarity, accuracy, and alignment with our internal quality and helpful-content standards. Learn more about our editorial review process.

Last updated: February 2026

Leave a Reply